Image and write-up by Nivretta Thatra

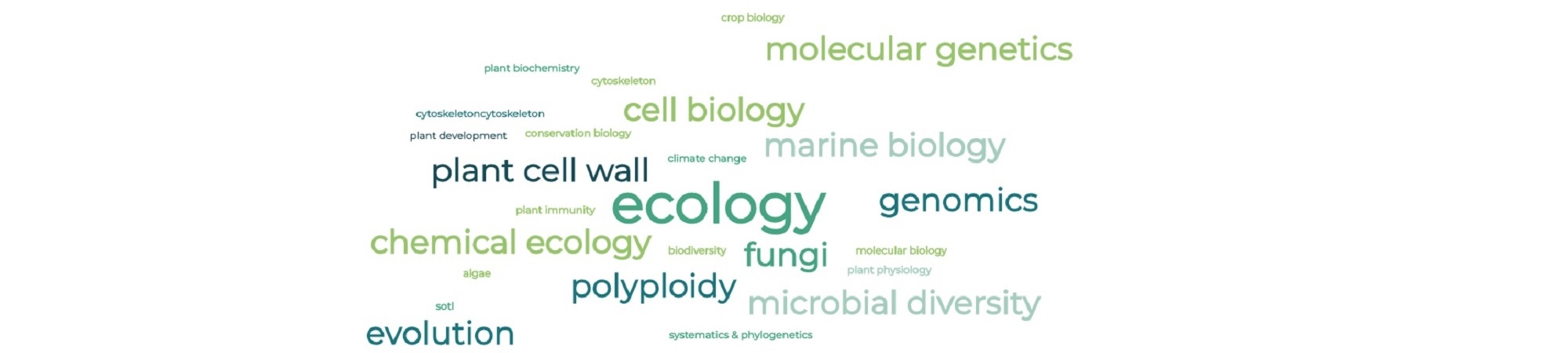

As of summer 2022, Dr. Alex Moore (she/they) is an Assistant Professor co-appointed at UBC Botany and the Faculty of Forestry. We are thrilled to be working with them!

Moore’s research programme currently focuses on predator-prey interactions in mangrove forests throughout the tropics and will begin to include restoration projects along the coast of BC. These are incredibly important, timely research goals, keeping in form with Moore’s previous experience working as a postdoctoral fellow with the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Given that description, seasoned scientists are likely to have a rough idea of the kinds of decisions and career transitions involved in Moore’s academic timeline. But for younger, newer scientists at the beginning of their journey, Moore’s path might seem hard to parse.

Read on to learn what Moore wants to share with young biologists — about their career path, how they learned research skills, and how work can align with community values.

To an outsider, it can seem like Dr. Moore has been on a linear, well-planned timeline to studying ecological conservation.

Moore elaborated on their timeline by stating that if someone had asked them ten years ago about where they would be now, they wouldn’t have been able to give a good answer. While they likely would have been able to envision themselves doing work related to conservation and the environment, they never would have guessed that they would be faculty.

“Each step along my academic timeline informed what I felt good about and what I didn’t feel good about doing in terms of what I wanted to do next,” they said.

Focusing on what was right in front of them – not what was ten years into the future – allowed Dr. Moore to be an intelligent and disciplined academic, and also gave them the space to figure out if they were enjoying the work. “At the beginning of my PhD I didn’t know what I’d be doing at the end of my PhD. All I was thinking about was, ‘I’m going to do my PhD,’” said Moore.

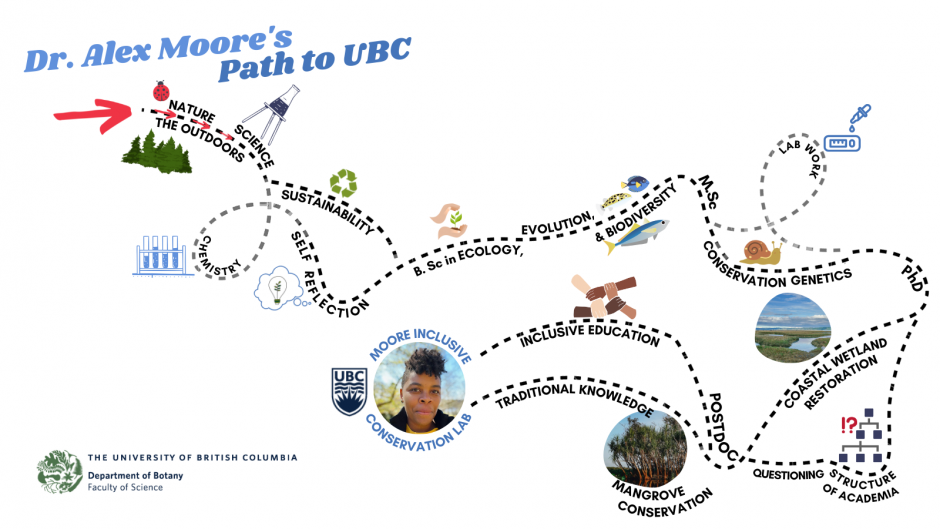

In fact, Dr. Moore’s path involved a few twists and turns. Check out the graphic above!

As an undergraduate, Moore started off as a chemistry major. It quickly became apparent that even though they earned high grades in the subject, they hated doing the work. Prompted by a sense of unease, they took time to self-reflect. When they thought about what they enjoyed doing and what they were drawn to, some themes arose: nature, spending time outdoors, and encouraging sustainable behaviors. Moore transitioned into the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology (EEB) major because the degree fit more of their interests.

They then did their Master’s degree in the same program (EEB), picking up key knowledge in conservation genetics and the transferable skill of lab work by working with a species of freshwater snails.

Learning wet-lab research skills was something Moore had to do on-the-fly while in their Master’s program.

“I had to do a lot to catch up to where everyone else was already starting,” said Moore. “People talk about the difficulty of getting into programs, and they also talk about the challenge inherent in academic spaces. But there is less conversation around where people think the starting line is, and whether or not you’re already at that starting point.”

Eventually, Moore realized they were not drawn to lab work. “I knew I was into conservation because I knew of my own personal connections to natural spaces and I knew that I wanted those spaces to persist into the future, but I didn’t really know how I wanted to fit into the field of conservation.”

While taking courses as a Master’s student, a class taught by Dr. Bradley Cardinale really caught Moore’s interest; the course examined the relationship between biodiversity, and ecosystems, and how people value and interact with natural systems. Moore was excited by how these topics prompted a diverse range of people to care about the science behind conservation. They carried this passion forward by incorporating species interactions and ecosystem services into their PhD research. During their PhD, Moore focussed on wetland ecosystems restoration in Connecticut. Instead of the more typical approach to trying to restore the physical parts of the system, such as nutrient availability via waterways, Moore incorporated the biological components of the system, such as interactions between predators and prey.

Moore’s PhD work showed that healthy ecosystem recovery is more likely when biological components of systems are incorporated into restoration. As a postdoctoral fellow, Moore expanded on this work by working on coastal mangrove restoration in the Pacific Islands, where they began to see the importance of traditional ecological knowledge and local environmental stewardship for ecosystems. These areas remain key to Moore’s current research.

However, Moore’s time as a PhD student also brought up some dislikes. They did not feel positively about the structure of academia, nor did their values align with the intense pressure to constantly publish. When pursuing postdoctoral opportunities, Moore decided to look for the opportunity to do “meaningful, impactful work that also supported equity, diversity inclusion for different kinds of communities of people.”

“The reason I took the postdoc position at American Museum of Natural History was because research was only one part of the role. The other part of my role was in teaching students from New York City who typically don’t have access to mentorship opportunities, and being able to do this spoke to the elements I felt were missing in my time in academia,” said Moore.

Moore’s journey through academia helped them identify the aims of the Inclusive Conservation Lab that they started when they arrived at UBC; they focus on applied community and ecosystem ecology research at various scales while incorporating the needs of local communities.

We concluded by asking Moore a few questions:

What would you say to a young scientist who doesn’t feel at home in academia?

Answer: I don’t know if it’s possible to really feel at home in an institution, and if it is possible, then it means that you’re aligned with whatever the institution is aligned with and maybe those alignments are problematic. I think what is possible is to feel at home in the community you decide to build within those spaces. When I was deciding where to do my PhD, a big element of my decision-making process was thinking through whether I would be in a space where I felt like I could have community. I had a terrible, terrible time in my Master’s program because I was brought into a non-inclusive space as a student in a non-traditional pathway; there were faculty members who didn’t think I belonged there or who weren’t convinced of the quality of my work.

While doing my PhD, I found home in people. You’ll always enter into an institutional culture that doesn’t align 100 per cent with your personal needs, but I think you can find trustworthy people that align with what makes you feel safe.

In your view, how did graduate school differ from the undergraduate experience?

Answer: While looking at graduate programs I was really aware of having to obtain financial support, the qualifying exam process, and coursework expectations. These all differ between institutions. I ended up choosing a program that felt right for me — my course load was low and the qualifying exam process was more involved but not as intense as other programs.

A challenge especially for young people coming into graduate spaces after the K-12 and undergraduate experience, where other people have structured your time for you, is being given the freedom to structure your own time while also being expected to complete a large scale research project. One thing you can do to establish some structure is to meet at the right intervals with your advisor. That interval, for me, was twice a month or once every couple weeks.

What is a commonly held belief about being a scientist that you want to dispel?

One of the big myths about what it takes to be a scientist is that you have to be “inherently” smart, that you have to be “inherently gifted”, or that you have to get the best marks on every standardized test you’ve ever taken.

Those things do not actually serve as metrics of whether or not you can be a good scholar. I don’t think that a certain background or mindset should disadvantage a person from being able to participate in this kind of scholarship, and I truly do think anyone could do this type of work with the right kind of support and with the right mentorship. I want more people to believe this!

Check out more of Moore’s work:

- Moore is co-teaching a course in January of 2023

- They are currently recruiting students to work with their Inclusive Conservation Lab in Winter 2023

- We encourage readers to watch a video interview with Moore, in which they expand on their goals for equity-driven research.