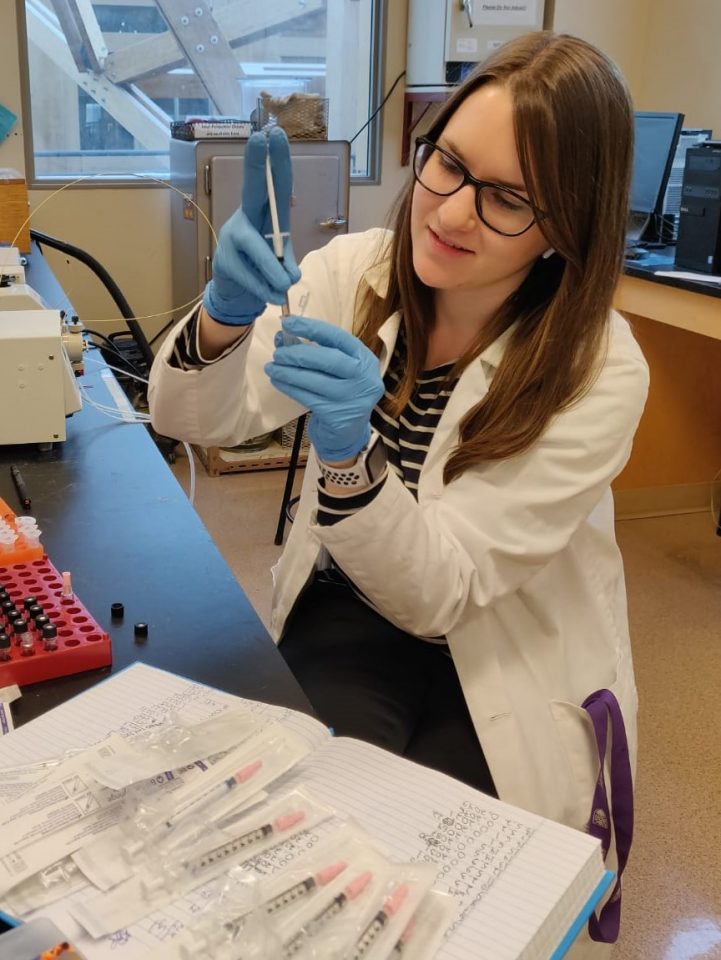

Elizabeth Mahon, PhD student in the lab group of Dr. Shawn Mansfield, was awarded the Jonathan Page Fellowship for her research on the biochemistry of the wood of poplar trees. The goal of her project is to engineer poplar trees for use as feedstock for renewable bioproducts like biofuels, pulp and paper.

The Jonathan Page Fellowship has allowed Mahon to enjoy doing research, including the process of problem-solving.

“Troubleshooting protocols and trying to figure out what’s working and what’s not working can lead to a lot of failure. When it does work it’s just the most satisfying and exciting feeling in the world,” said Mahon. “The fellowship is allowing me to complete the last year of my research and finish my thesis without feeling like I’m under pressure.”

Below is our conversation with Elizabeth Mahon where she discusses the details of her work, her rewarding experiences working with tricky protocols, and her thoughts on the mental burdens of graduate school.

What is the key question of your research?

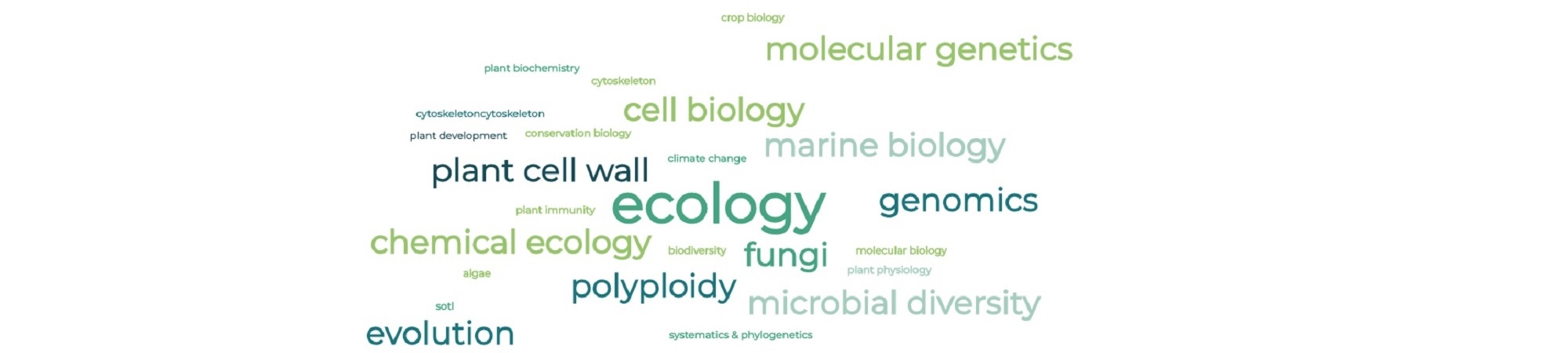

Mainly, I’m interested in how we can modify the metabolism of phenolic compounds in the developing xylem of poplar trees to improve poplar as a feedstock for bioproducts like biofuels, pulp and paper.

The wood of trees is made of biopolymers, such as lignin and cellulose. I work on lignin, which is the biopolymer that makes wood strong and allows trees to stand up. I am introducing new chemicals that are normally found in grass lignin into the poplar trees using genetic engineering. This could make the lignin more easily extracted from trees for use in bioproducts. As a team, we work on trying to understand how the cell wall is assembled naturally in a growing tree, as well as how we can modify the component parts to improve the biomass’s characteristics for certain uses.

How did you end up working on poplar trees in Dr. Mansfield’s lab?

When I first started as an undergrad, I decided to just take a bunch of different general science classes to see what I was interested in. I really enjoyed genetics problem sets like the ones involving Punnett squares. Maybe I already had inclinations towards problem-solving at that point, but I think as an undergrad I was employing such a different set of skills that it wasn’t until I started doing directed studies in my third and fourth year that I got a taste for the hands-on problem-solving part of research.

I decided to do my Master’s work in the same lab where I completed my directed studies.I did my Master’s degree on pine trees; I was working at the University of Alberta within the field of forestry using genetics to better understand the defense response to mountain pine beetles. Moving into my PhD, I knew that I wanted to stay within the realm of forestry, and I really wanted to be able to work with a species that I could genetically manipulate. Poplar is a really unique tree species in that it is very amenable to genetic transformation. Poplar is also a very productive tree and grows very well in Canada.

Additionally, after my Master’s, I became more interested in population genetics and I knew I wanted to come to UBC Botany – it’s one of the biggest plant science programs in Canada! All those factors initially drew me to work with Dr. Carl Douglas, who at the time was utilizing bioinformatics techniques to examine almost 400 different unique popular genotypes to find particular loci that contribute to wood characteristics. He unfortunately passed away the summer before I came to UBC. I really wanted to continue on with the poplar project he had started. I contacted Dr. Sean Mansfield, who specializes in genetic manipulation in the context of forestry, and he agreed to take me on as a student with the research focus I’d already chosen.

You’ve described that poplar species are attractive as model organisms for multiple reasons. Does this mean that it has been easy to work with poplar species in the lab?

In the Mansfield lab, I got lucky in that there is a really well-established protocol for genetically transforming poplar to introduce novel genes. Where things got complicated was when I started doing biochemical characterization of enzymes, which hadn’t been done in our lab frequently. To trouble-shoot the experimental protocol, I couldn’t find anything from online databases that could work with the equipment we had in the lab. Finally, I found a protocol in an actual physical book published thirty years ago which was very satisfying! Even though it took three months of work, it felt really rewarding when everything came together in the end.

Describe a key value of yours that you’ve identified from your time as a student.

One thing I’ve learned throughout my degree, which a lot of people are echoing right now, is the importance of mental health. When you’re doing your PhD, you can get so wrapped up and so focused on that one thing. Completing a graduate degree is a very challenging thing to do; it challenges you intellectually but also challenges your mental wellbeing.

Making sure that mental health is a priority is something that I take really seriously. It’s very important to me as an older student in my lab to encourage conversations around wellbeing with newer graduate students. I also extend this perspective to the undergraduates in my lab. It’s really fun to see new undergrads come into the lab and get the chance to actually apply their knowledge beyond studying for tests. Once they get their feet under them, I try to help them enjoy their experience while also learning a lot along the way.

What has been challenging in your scientific journey?

My feeling and the feeling of a lot of students who are close to graduation is that there is simply not a lot of certainty about staying in academic careers. About 25% of the students who graduate from UBC Botany get tenure-track academic jobs. Throughout your degree you can feel as if you’re on a singular track to a position in academia, and when you get to the end you begin to realize that that career path is not as clear as it used to be historically, or as clear as what you thought initially. There can be pressure and negativity as well as reward and positivity in facing the fact that while most of your mental energy is being occupied by getting your research done and writing it up, you do have to have to consider what you’re going to do afterwards.

The mentors I’ve had at UBC Botany have been very encouraging of me exploring different career paths. I work a lot with Dr. Lacey Samuels and her lab; I appreciate that she encourages students to go down whichever path is best for them. I’ve been able to see what other students who’ve recently graduated have gone on to do, which has helped me realize that I don’t have to stay within academia. Many students have gone on to have really fascinating jobs and that relieves a lot of the pressure.

When you’re not focused on research, what do you like doing?

My partner and I both really like to swim. I was on the UBC Masters swim team for a while, but they’re not practicing regularly because of COVID. I recently started open water swimming with my partner at Kitsilano Beach in the summertime, and we both enjoy heading to the pool during the winter.